Shim is a critical middleware component used in operating systems. Through API interception or signature verification, it provides both application compatibility and Secure Boot integrity. However, it can also serve as an attack surface for threat actors. This article focuses on the design, implementation, potential security risks, and defense strategies related to Shim.

Introduction: What is a Shim?

In computing, a Shim acts as an intermediary layer that bridges the gap between two incompatible system components. Much like a gasket in mechanical engineering, a shim fills in the space or mismatch, enabling smooth interaction.

In computer systems, shims vary in form but share the core goal of modifying or intercepting native behavior to enable compatibility or enforce security. This article explores Shim implementations in two major OS platforms:

- Windows - Application Shim: Primarily for resolving legacy software compatibility.

- Linux - Secure Boot Shim (UEFI environments): Serves as the foundational trust anchor in the Secure Boot chain.

Comparing Shims in Windows vs. Linux

| Aspect | Windows Application Shim | Linux Secure Boot Shim |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Compatibility for legacy apps | Trust anchor for Secure Boot |

| Runtime Context | User-mode | Early UEFI boot phase |

| Main Function | API interception, behavior modification | Digital signature verification (GRUB, Kernel) |

| Installation | .sdb database, tool-assisted |

Signed loader (distro-shipped, Microsoft-signed) |

| Security Risks | Shim Injection | Vulnerable outdated shim bypassing Secure Boot |

| Common Use Case | Internal legacy systems, old games | Dual-boot systems, cloud Linux images |

Windows: Implementing Application Compatibility Shims and Security Implications

1. Use Cases & Purpose

Windows Shims are designed to resolve compatibility issues that arise when older applications are run on newer OS versions. By intercepting API calls, the shim can masquerade version behavior or adjust logic, tricking the app into “believing” it’s still in a legacy environment.

2. Core Mechanism

- Shim Database (

.sdb): Maps applications to associated fixes. - Shim Engine: Injects DLLs and intercepts runtime APIs.

- Compatibility Administrator: GUI tool for customizing and deploying shim fixes.

3. Example Command to Install a Shim

1 | # After creating the `.sdb` file using the Compatibility Administrator tool |

4. Querying Installed Shim Databases

For Older Versions of Windows:

If you’re using an older version of Windows (e.g., Windows 7 or 8), you can check for installed custom .sdb (Shim Database) files using the following PowerShell command, as documented in earlier technical references (Ref. [1][2]):

1 | reg query "HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\AppCompatFlags\InstalledSDB" |

For Newer Versions of Windows:

On more recent versions of Windows (e.g., Windows 10 or 11), the above registry path may not exist or may return nothing. This is because while the AppCompat database still exists, its entries are no longer guaranteed to appear under the InstalledSDB key. Instead, related Shim information may be spread across other registry locations.

You can use the following PowerShell commands to check for relevant Shim behaviors:

List custom shims applied to specific executable paths:

1

reg query "HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\AppCompatFlags\Custom"

List user-defined compatibility layers, such as those set via “Run in compatibility mode” from the right-click menu:

1

reg query "HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\AppCompatFlags\Layers"

Why Might the InstalledSDB Key Be Missing?

There are several possible reasons why the InstalledSDB key is not found in newer versions of Windows:

- Not all .sdb installations are recorded under InstalledSDB.

- Some Windows editions no longer create this registry key by default.

- Microsoft has shifted its approach to managing shims, increasingly favoring stricter application control mechanisms such as WDAC (Windows Defender Application Control) and AppLocker.

5. Common Shim Examples

VersionLie: Fakes Windows versionForceAdminAccess: Tricks apps into thinking user is AdminCorrectFilePaths: Redirects paths to compatible locations

6. Security Risk - Shim Injection

Attackers can craft .sdb files and use sdbinst.exe to silently install malicious shims. When the target application runs, the shim injects malicious logic. Notably, the APT group FIN7 has used this technique for persistent access. (Ref.[3])

Linux: Shim’s Role in Secure Boot

1. Secure Boot Overview

UEFI Secure Boot ensures only signed binaries are executed during boot. Firmware trusts binaries signed by Microsoft’s UEFI CA.

2. Why Linux Needs Shim

Shim allows distributions to sign and manage their own GRUB/kernel updates without requiring direct Microsoft signature for every update.

Shim itself is Microsoft-signed, while embedded public keys inside shim verify GRUB and Linux kernel.

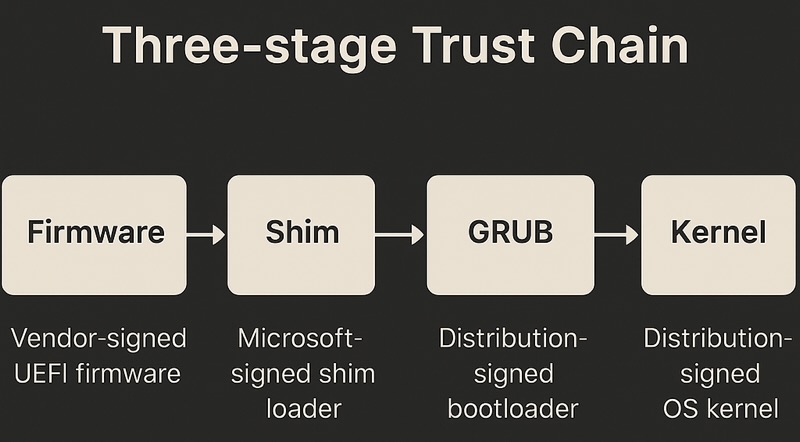

3. Boot Process Flow: The Shim Three-Stage Trust Chain

The three-stage trust chain is a core architecture used in Linux systems under UEFI Secure Boot to ensure a secure and tamper-resistant boot process.

Its primary goal is to guarantee that every executable component involved in the boot sequence—from UEFI firmware to GRUB and ultimately to the Linux kernel—is cryptographically verified and trusted, ensuring integrity and authenticity throughout the chain.

This trust chain consists of four critical components in sequence: Firmware, Shim, GRUB, and the Kernel. Each stage is signed and verified by a distinct trusted authority:

- Firmware is typically provided and signed by the hardware vendor.

- Shim is developed by the Linux distribution and signed by Microsoft to gain acceptance by the UEFI firmware.

- GRUB and the Kernel are signed by the distribution itself and are verified by Shim using embedded public keys or through the MOK (Machine Owner Key) mechanism.

Together, these components form a complete and auditable trust path, ensuring that only validated binaries are executed during system boot.

Detailed Flow:

Step 1: Firmware → Shim (Signed by Microsoft)

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Boot Source | UEFI firmware |

| Target | shimx64.efi (provided by the Linux distribution, signed by Microsoft) |

| Verification | Verified via Microsoft UEFI CA signature |

| Purpose | Enables non-Microsoft bootloaders (e.g., GRUB) to load under Secure Boot |

Step 2: Shim → GRUB (or Other Bootloaders, Signed by Distro)

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Boot Source | shimx64.efi |

| Target | grubx64.efi (signed by the Linux distribution) |

| Verification | Verified using an embedded public key in Shim, or via the MOK (Machine Owner Key) system |

| Purpose | Loads the next-stage bootloader (e.g., GRUB) and establishes the next trust link |

Step 3: GRUB → Kernel (Using Shim’s Verification Capabilities)

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Boot Source | GRUB |

| Target | vmlinuz (Linux kernel image) |

| Verification | Verified using the signature checking modules from Shim or GRUB |

| Purpose | Ensures that the kernel being booted is cryptographically validated |

These three stages are jointly managed by Microsoft, the Linux distribution, and the system owner, forming a complete and layered trust architecture based on tiered signing and staged verification.

4. Managing Custom Keys: MOK (Machine Owner Key)

MOK (Machine Owner Key) allows users to manually enroll custom signing keys, which can then be used to validate third-party drivers or custom-compiled Linux kernels.

Once enrolled, the corresponding public key is stored in NVRAM (non-volatile memory) and becomes part of the Secure Boot validation process, handled by MokManager during system startup.

Example: Importing a MOK on Ubuntu

1 | sudo mokutil --import my_key_pub.der |

5. Security Retrospective: BootHole and the Birth of SBAT

The disclosure of the BootHole vulnerability (CVE-2020-10713) in 2020 marked a turning point for the UEFI Secure Boot ecosystem.

This flaw existed in the configuration parsing logic of the GRUB2 bootloader, where an attacker could tamper with grub.cfg to inject malicious code. Alarmingly, this could occur even with Secure Boot enabled, effectively bypassing the signature verification process and executing unsigned binaries.

This incident exposed a critical single point of failure within the Secure Boot trust chain and highlighted the limitations of the traditional revocation approach (such as Microsoft’s dbx blacklist), where revoking a single vulnerable binary could inadvertently disrupt all systems using that version.

To address these systemic risks, the Linux community—in collaboration with UEFI stakeholders such as Canonical, Red Hat, and others—developed a new mechanism called SBAT (Secure Boot Advanced Targeting).

SBAT introduces a more granular and version-aware revocation model, enabling Secure Boot to selectively block specific versions of vulnerable boot components—such as particular builds of shim, GRUB, or the Linux kernel—without impacting safe versions. This significantly improves the flexibility and maintainability of Secure Boot over time.

Conclusion: Shim as a Double-Edged Sword

Shim plays a bridging role in modern operating systems:

- In Windows, it extends the lifecycle of legacy applications by ensuring compatibility.

- In Linux, it upholds the integrity and continuity of the Secure Boot trust chain.

Only by thoroughly understanding how Shim works can organizations fully leverage its advantages—while proactively mitigating the potential security risks it may introduce.

Why Is Shim Considered a Double-Edged Sword?

Pros:

- Maintains Compatibility and Flexibility:

Shim offers significant flexibility and operational convenience, allowing legacy applications or custom drivers to continue running in modern environments. This reduces both maintenance overhead and the cost of system upgrades.

Cons:

- Potential Security Risks:

The same mechanisms that offer flexibility can also be exploited as attack vectors. For example, malicious actors may leverage Shim Injection in Windows or exploit outdated shims in Linux to bypass security controls. - Single Point of Failure in the Trust Chain:

In Secure Boot environments, Shim serves as the root of trust. If Shim itself is compromised—either by a vulnerability or unauthorized replacement—the entire trust chain may be invalidated. - High Maintenance and Revocation Complexity:

Once widely deployed, updating or revoking Shim (e.g., via SBAT) can be operationally challenging. Improper updates may even prevent systems from booting, increasing the risk and complexity of incident response.

Mitigation Strategies and Security Recommendations

For real-world deployment, organizations and developers are strongly encouraged to implement version control, enforce signature policies, and adopt centralized management solutions. Continuous monitoring of Shim and Secure Boot–related security advisories is essential to reduce potential attack surfaces.

Recommended actions include:

Maintain Compatibility with Controlled Flexibility

- Apply Shims only to essential legacy applications where no viable alternatives exist, avoiding unnecessary dependency across the system.

- Implement a robust change management and testing process (e.g., following ISO/IEC 27001, NIST 800-53), including risk assessment, functional validation, and version tracking for each Shim configuration to balance compatibility with security.

- Enforce application whitelisting policies using mechanisms such as AppLocker or WDAC to restrict the execution of unauthorized programs.

Address Potential Security Breaches

- Establish monitoring systems to detect suspicious behavior such as the execution of sdbinst.exe or unusual changes to Shim databases.

- Restrict Shim installation privileges to system administrators and limit access to Shim-related tools at the user level.

- Conduct regular audits of %WINDIR%\AppPatch\Custom\ and relevant Shim-related registry paths to track unauthorized modifications.

Mitigate Trust Chain Single Points of Failure

- Use only officially distributed Shim binaries signed by Microsoft to ensure integrity and trustworthiness.

- Deploy SBAT-compliant Shim versions, which allow for granular revocation and precise version management.

- Maintain up-to-date versions of Shim, GRUB, the Linux kernel, and UEFI firmware to reduce exposure to known vulnerabilities.

Reduce Operational Overhead and Improve Revocation Response

- Utilize centralized management tools such as Microsoft Intune or Ansible to streamline deployment and monitor Shim usage across environments.

- Design boot recovery strategies, including USB live images or dedicated recovery partitions, to ensure system bootability in case of Shim-related failures.

- Maintain version history and SHA-256 checksum records to support validation and forensic investigation when needed.

References

- Black Hat EU 2015 Whitepaper - Defending Against Malicious Application Compatibility Shims

- F-Secure Blog Post - Hunting for Application Shim Databases

- Google Cloud - FIN7 Leveraging Shim Databases

About this Post

This post is written by Kevin Chiu, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.