This article explores how organizations can translate the six core functions of CSF 2.0 into actionable, governance-driven incident response strategies — from the perspective of a Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) or senior cybersecurity executive.

Introduction

NIST SP 800-61r3, officially titled:

Incident Response Recommendations and Considerations for Cybersecurity Risk Management: A CSF 2.0 Community Profile,

was released in April 2025 by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

As part of the NIST 800-series standards, it focuses specifically on incident response management, aiming to help organizations build and enhance their incident response plans in alignment with the latest cybersecurity risk management practices and framework requirements.

Today’s digital landscape — shaped by supply chain breaches, ransomware-as-a-service models, and sprawling multi-cloud environments — has outgrown traditional incident response playbooks. NIST SP 800-61r3 steps in not just as a procedural update-but as a governance playbook for enterprise-wide cyber resilience.

Unlike previous versions that focused primarily on technical procedures for handling incidents, the SP 800-61r3 update reframes Incident Response (IR) as an integral part of an organization’s cybersecurity risk governance. More importantly, it fully aligns IR practices with the updated NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0.

At its core, the biggest shift isn’t technical — it’s cultural. It’s about how organizations think, act, and lead when cyber risk strikes.

In addition, the NIST 800-series publications represent one of NIST’s most comprehensive sets of guidance for information security, covering a wide range of topics including risk assessment, access control, and privacy protection. SP 800-61r3, in particular, focuses on the specific domain of cybersecurity incident response strategies.

Rethinking Incident Response Through the Lens of CSF 2.0

To understand how incident response is evolving, we need to start with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0.

This updated framework organizes cybersecurity governance into six core functions — each tightly connected to how organizations prepare for, respond to, and recover from cyber threats.

| Function | Description | Role in Incident Response |

|---|---|---|

| Govern (GV) | Policy and governance | Define IR roles, responsibilities, and authority |

| Identify (ID) | Asset and risk discovery | Understand what’s at risk and identify threat models |

| Protect (PR) | Proactive defense | Minimize likelihood and impact of potential threats |

| Detect (DE) | Monitoring and detection | Recognize anomalies, malicious behaviors, and breaches |

| Respond (RS) | Response execution | Communicate, contain, and remediate incidents |

| Recover(RC) | Service restoration and learning | Restore services and strengthen future defenses |

From Process-Driven to Governance-Led: A Shift in Incident Response Mindset

To truly understand the shift introduced in SP 800-61r3, it helps to compare it with the previous version, SP 800-61r2, published back in 2012:

| SP 800-61r2(2012) | SP 800-61r3(2025) |

|---|---|

| Incident response (IR) was treated as a standalone cycle: Preparation → Detection → Containment → Recovery |

IR is now fully integrated into the broader risk management lifecycle of CSF 2.0 |

| Emphasized technical procedures and sequential stages | Focuses on cross-functional governance and organizational integration |

| Prioritized forensics, technical investigation, and root-cause analysis | Highlights clear roles, decision-making authority, and a security-aware culture |

| Included detailed procedural guidance within the document | Delegates implementation details to tools like CPRT, while focusing on strategic thinking and principles |

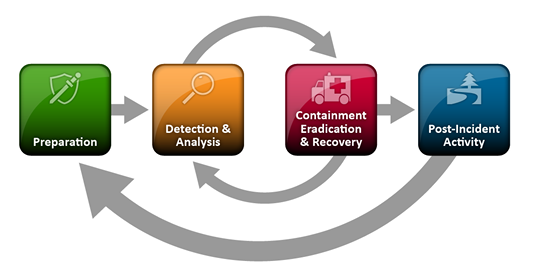

Under SP 800-61r2, incident response was structured as a closed-loop cycle with four primary phases:

- Preparation – Laying the groundwork with plans, tools, and training to enable effective response

- Detection and Analysis – Rapidly identifying and assessing the scope and impact of an incident

- Containment, Eradication, and Recovery – Controlling the spread, removing the threat, and restoring operations

- Post-Incident Activity – Reviewing what happened, capturing lessons learned, and improving future response capabilities

Ref. NIST SP 800-61r3

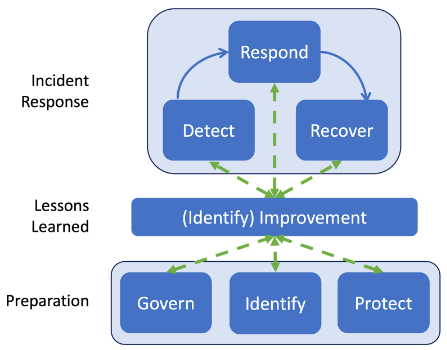

In contrast, SP 800-61r3 aligns incident response with the six core functions of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0. Instead of a static, step-by-step cycle, the new model introduces a flexible, governance-driven approach — one that treats incident response as a continuous and dynamic part of enterprise-wide cybersecurity risk management.

Ref. NIST SP 800-61r3

Here’s how the old lifecycle maps to the updated model within the CSF 2.0 context:

| SP 800-61r2 Lifecycle | Mapped to SP 800-61r3 (with CSF 2.0) |

|---|---|

| Preparation | - Govern - Identify (all Categories) - Protect |

| Detection & Analysis | - Detect - Identify (Improvement Category) |

| Containment, Eradication & Recovery | - Respond - Recover - Identify (Improvement Category) |

| Post-Incident Activity | - Identify (Improvement Category) |

Governance in Action: Aligning IR Strategy with the CSF 2.0 Core Functions

Govern

Focus: Clear roles and explicit authority

- Define and maintain incident response policies, including classification, escalation, and accountability(GV.PO-01)

- Clarify roles and responsibilities across internal teams and third-party vendors(GV.RR-02)

- Establish communication pathways with HR, Legal, PR for coordinated response to high-impact incidents

Together, these governance practices transform IR from a siloed IT task into a top-down, organization-wide responsibility with clear escalation and accountability mechanisms.

Identify

Focus: Asset inventory and risk awareness

- Maintain a complete asset inventory (IT/OT/cloud/hardware/software/supply chain) (ID.AM series)

- Conduct ongoing risk assessments and threat modeling(ID.RA series)

- Institutionalize lessons learned into IR planning (ID.IM series)

This enables more accurate threat anticipation and deeper understanding of potential blast radii in case of incidents.

Protect

Focus: Proactive defense and exposure reduction

- Enforce least privilege and strong identity controls (e.g., MFA)(PR.AA-05)

- Ensure effective backup and disaster recovery to mitigate ransomware impact(PR.DS-11)

- Harden systems and establish logging/retention policies(PR.PS-04)

Defense readiness is no longer optional-it’s the foundation of incident impact control.

Detect

Focus: Let anomalies surface, don’t wait for damage

- Deploy continuous monitoring across network, cloud, and user behavior(DE.CM series)

- Integrate CTI, SIEM, and SOAR tools for correlation and detection (DE.AE-07)

- Establish clear escalation paths and severity grading(DE.AE-08)

When teams can see what’s happening in real time, they’re not just faster — they’re smarter. Escalations are spotted earlier, and decisions happen when they matter most.

Respond

Focus: Preparedness and execution

- Define a multi-tiered response and decision framework(RS.MA-02、RS.MA-03)

- Enable joint operations with CSPs, MSSPs, and external responders

- Maintain evidence and log all response actions for forensics and retrospectives(RS.MA-04)

The shift to operational readiness empowers teams to act-not react-in critical moments.

Recover

Focus: Recovery is more than rebooting

- Integrate recovery planning with BCP/DR strategies (RC.IM series)

- Validate asset integrity and data trust before restoration

- Conduct post-incident reviews to continuously strengthen future responses

Recovery is no longer the final step-it’s the bridge to resilience and adaptive learning.

Supporting Tools and Additional Resources

- CPRT

- Full Title:Cybersecurity and Privacy Reference Tool

- Purpose:A tool for mapping NIST controls and identifying relevant examples.

- Use Case:Enables users to look up specific NIST control mappings, implementation use cases, and technical references for practical application.

- SP 800-150

- Full Title:Guide to Cyber Threat Information Sharing

- Purpose:A guideline for applying cyber threat intelligence (CTI) practices.

- Use Case:Designed to support the design and integration of CTI sharing and collaboration mechanisms across organizations.

- SP 800-84

- Full Title:Guide to Test, Training, and Exercise Programs for IT Plans and Capabilities

- Purpose:A handbook for conducting cybersecurity incident simulations and training.

- Use Case:Useful for developing attack scenarios, tabletop exercises, and standard operating procedures (SOPs) for incident response.

- SP 800-218

- Full Title:Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF) Version 1.1: Recommendations for Mitigating the Risk of Software Vulnerabilities

- Purpose:Provide a set of recommended practices for integrating security into every phase of the software development life cycle (SDLC)

- Use Case:A structured framework for secure software development and supply chain risk management.

Strategic Priorities for Modernizing Incident Response

NIST SP 800-61r3 makes it clear:

Incident Response is no longer an isolated technical task-it is a pillar of enterprise risk governance.

To effectively modernize their incident response and risk strategies, organizations should prioritize the following actions:

- Align IR planning with the six CSF 2.0 functions to create a collaborative, organization-wide response model.

- Regularly update risk assessments, threat playbooks, and scenario simulations.

- Adopt automation and orchestration tools (e.g., SOAR) to boost response speed and efficiency.

- Institutionalize post-incident review as a routine process, not an afterthought.

Leadership and Board Considerations

Executives and board members must ensure that incident response capabilities are not only resourced but embedded into organizational performance metrics, such as operational resilience KPIs and audit readiness.

Final Thoughts

There was a time when incident response felt like putting out fires – someone clicked a malicious phishing link, the internal network got compromised, and suddenly it’s 2 a.m. with SOC alarms blaring. We’d dive in, stop the bleeding, clean up the mess as best we could, write up the report, and hold the line until the next crisis came around.

But that model simply doesn’t cut it anymore. Today, a single security incident isn’t just a technical issue – it’s a full-blown business crisis. What follows isn’t just system recovery, but a chain reaction: regulatory scrutiny, plummeting customer trust, reputational damage, and a boardroom demanding answers.

That’s why incident response can no longer be treated as an isolated technical task or a one-off procedural cycle – it must be embedded into the core of organizational governance – designed from day one as part of the organization’s risk strategy, embedded into planning, rehearsed regularly, and executed with precision.

Real maturity isn’t about how many policies you’ve written or how detailed your workflows are. It’s about how your teams respond when things go wrong – with clarity under pressure, speed in decision-making, and a willingness to take ownership.

NIST SP 800-61r3 isn’t just a rework of flowcharts or an update to templates. It’s a signal that the bar has been raised: cybersecurity governance is shifting from fragmented procedures to holistic integration.

Resilience doesn’t come from tools alone – it’s built through a culture of unified action. When SOC analysts, IT leaders, operations teams, suppliers, and executives can respond as one – not in silos – that’s when true readiness takes root.

Because in the end, resilience isn’t about how polished your roadmap looks. It’s about how your team responds when that roadmap no longer applies – whether they can pivot fast, hold their ground, and steer the business through the storm.

Further Reading

About this Post

This post is written by Kevin Chiu, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.